Should you get your PhD?

“I’ve never felt so much in my element”

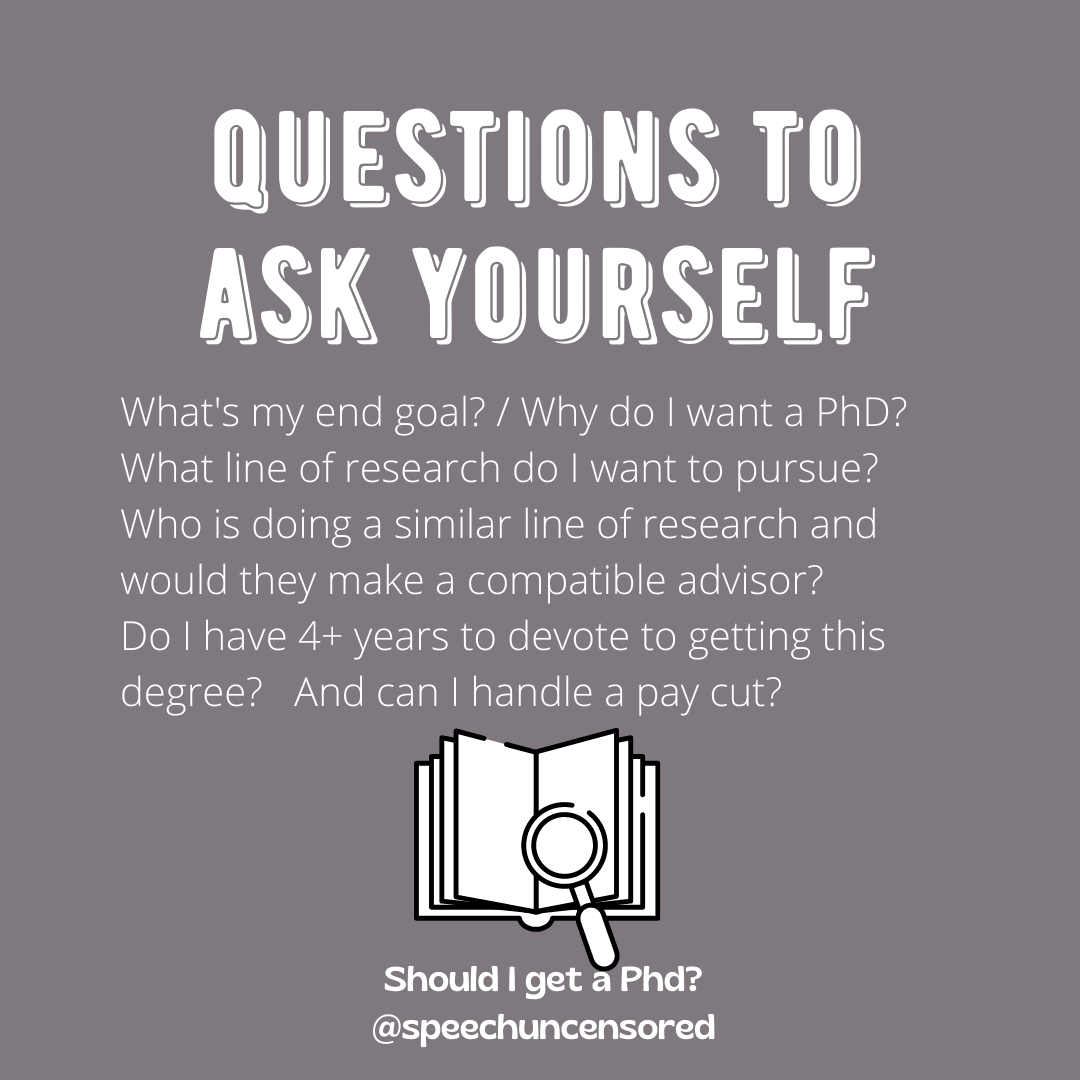

At some point, we’ve all thought about it. But what actually goes into earning a PhD in the Communication Sciences and Disorders (CSD) field? And what can you do with it once you’ve earned it? At a junction point in my career, I started to seriously consider pursuing a PhD and thinking about what’s next on my career path.

Here’s what I did:

Talked to A LOT of people. I interviewed PhDs, SLPDs, EdDs, professors, business owners with PhDs, clinical instructors, PhD students, and researchers. I got a lot of similar information (the basics) but each one had a unique perspective which proved invaluable in helping me make my decision.

I have an 11-page, single-spaced document of notes from 6 interviews I conducted. I have plans to reach out to more people and add to that document. The irony of researching a research degree is not lost on me.

Read about it! I found a great book at a used bookstore called “How to survive your PhD” that made me sit down, think, and write out my purpose, my wishes, and my future plans. Oddly, I hadn’t done that before and it was crucial in figuring out what’s next for me.

Another book recommended was “The Unwritten Rules of PhD Research.”

Checked out ASHA’s “Considering and Pursuing a PhD in Communication Sciences and Disorders” page. Lots of good information to get your feet wet.

Went down a RABBIT HOLE of online research of university PhD programs. A word to the wise… take notes as you look through the 83+ programs listed on ASHA’s “EdFind.” One specific professor in a line of research appealed to me, and now I can’t remember where I saw her or what her name was exactly. This will haunt me for the rest of my days.

“Spend some time reflecting on your purpose for pursing a PhD. I found this a very helpful exercise. ”

“Something I wish I knew: a PhD does not prepare you for academia - it prepares you for research.”

Here’s what I learned:

A PhD is training for a WHOLE NEW JOB. This is especially relevant to me, as a practicing clinician who enjoys working with patients. If I get a PhD, I am trading clinical work for research/teaching/service.

Every PhD program is different. There are similarities (ex. you will take statistics at every CSD PhD program), but each program is unique to the department and the PhD student.

Most people with PhDs go into academia and become professors. But you don’t have to. I know some who are business owners or work clinically.

A PhD is a research degree - you will do research. And statistics. Be prepared to get intimate with both.

A PhD is a marathon - the smartest don’t always finish - it’s the people who can persevere, stay true to the course, and do the durn thing.

Find and interview an advisor who not only fits your research goals, but who you actually like and can get along with for the next 4+ years. They have immense power over your PhD career. Getting your PhD is hard enough, avoid adding a difficult relationship to the mix.

DO NOT PAY TUITION FOR YOUR PHD IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCES AND DISORDERS. This was often repeated to me by the PhDs I interviewed and the resources I read. There should be funding available to cover your tuition at a minimum. Often there are stipends to cover health insurance as well. Additionally, you will likely work (in the research lab, teaching, or supervising) for 20 hours a week and get a small stipend from the university. Every program is different - so be sure to ask about funding.

By the way - getting your PhD fully funded does not apply to online programs. Online programs are built to accommodate working professionals. Online programs are a topic for another post.

Reach out and talk to multiple professors who are involved in lines of research that interest you. One of them might end up as your advisor. There is an unwritten rule that you need to secure an advisor BEFORE you apply for the PhD program.

It was recommended to me that you meet with and interview each potential advisor in person. The person shared that all the email communications were really positive, but when the SLP met the potential advisor in person, it turned out to not be a good fit. The SLP felt like she dodged a bullet.

Reach out and talk to the coordinator for PhD programs at universities you’re interested in. Another unwritten rule is reach out and begin that relationship BEFORE you submit an application.

There is an opinion out there that the advisor matters more than the program or the university you attend for your PhD. The advisor can make or break your PhD.

Speaking of advisors - I also learned that if the advisor has mentored others - then you join a ‘family’ of PhDs, connected by this shared experience and similar research interests. They are often very helpful to reach out to and supportive during your PhD journey. This not only benefits your PhD course, but your future career as well.

“Mentorship is the most valuable thing you negotiate for in your PhD career.”

The ugly side of getting your phd

Nothing is perfect in life, and there is a downside to everything. Here’s a snapshot of what I’ve learned so far:

Egos are a thing. Tread lightly. Be humble.

Supplicate with food if necessary (a recommendation from the book I read. The book was written by a man. I was surprised by this suggestion. But I can’t argue with it. I like food.).

Online programs are not looked on as favorably as in-person programs.

Only 1% of the population has a PhD. That might explain why there’s a certain level of snobbery prevalent in academia.

You will sacrifice 4+ years of your life in the pursuit of a degree. When you achieve the degree, you will start at the bottom of the hierarchy at your university job.

There’s a strong likelihood you will not achieve the degree. There’s even an acronym for it: ABD - all but dissertation. People proceed through the first two years of study (courses), and then fizzle out when it comes to writing and defending the dissertation.

“The most important thing is to know what you want to do with the degree. Once you know your end goal, you will know if a PhD, EdD, or SLPD/clinical doctorate is right for you.”

special thanks

I am indebted to Meredith, Rebecca, Fe, Bonnie, Amanda, and Lindsey for taking the time to share their insights with me and provide guidance on my journey to PhD or not. Deepest thanks!