Hacking the ACT for Low-Level Patients

The material on this page will only make sense if you have a pretty good understanding of where I stand on EBP, hacking EBP, and patient-centered care. If you’ve already read those posts, then keep right on going and scroll on down to the good stuff! If not, then I recommend reading these articles first by clicking the images.

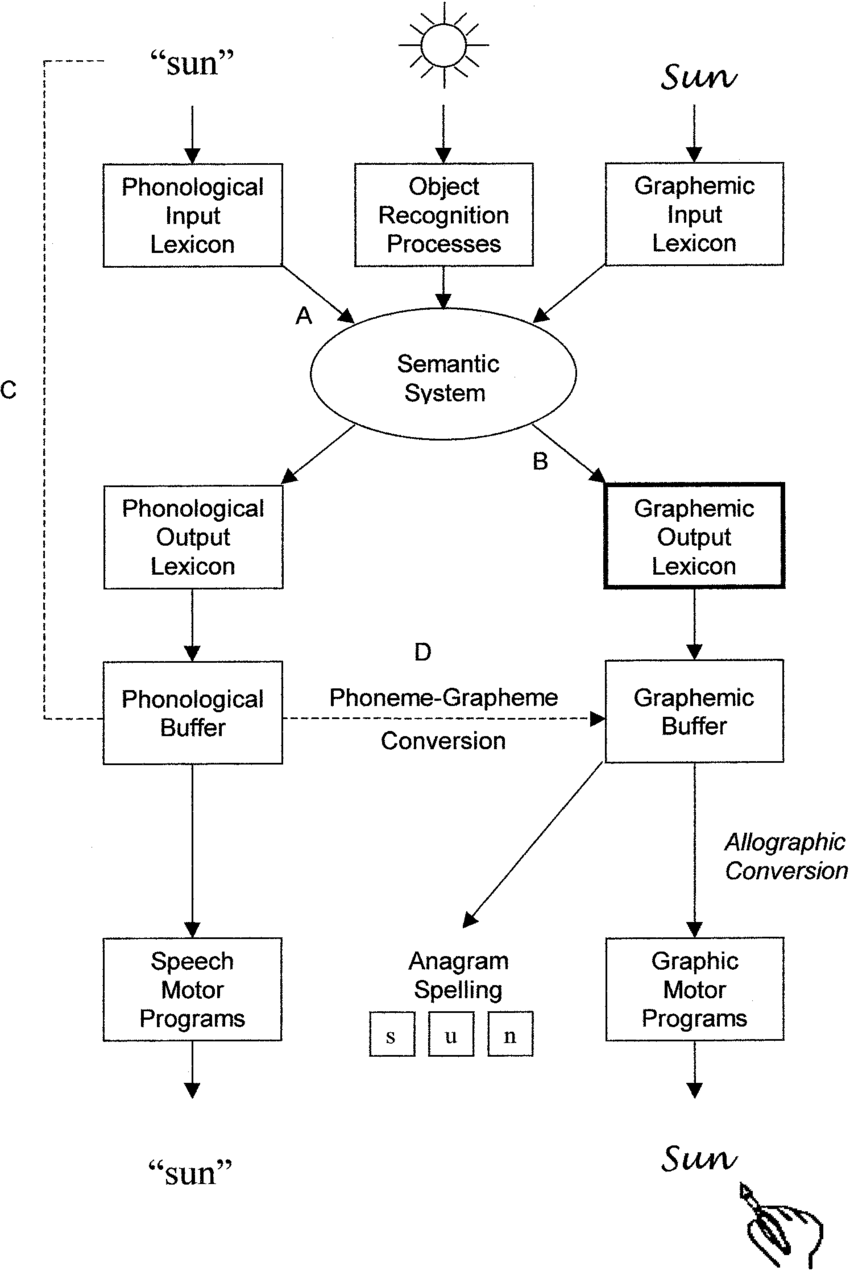

“A Cognitive Model of Language Processing” From Beeson et. al. 2002

Here is a case study of hacking ACT for a patient with global aphasia, verbal apraxia, and monoplegia of the right arm (right dominant at baseline). The patient experienced a stroke and completed extensive therapy at multiple levels of care for about a year. I am seeing this patient and spouse after they took a year “hiatus” from structured therapy, so approximately 2 years since the stroke. At time of evaluation, the patient only has one phrase they are able to produce. This stereotypical utterance is used in place of all other utterances. The patient has a high-tech communication device, however they do not use it regularly. The patient’s spouse encourages verbal communication attempts and is supportive of the patient’s communication needs. They have returned to therapy because the spouse is concerned that if something happens to him, the patient won’t be able to make their wants or needs known.

This is a very brief history, a lot of pertinent details are omitted. My goal is to set the stage so you can see a real world application of the modification of a treatment modality. I’m not interested in presenting a play-by-play on how to treat a patient presenting with x, y, z deficits resulting from a, b, c lesions as described on an MRI or CT scan. Because 10 different therapists would likely take 10 different treatment approaches and each of them would have great outcomes.

I chose the ACT for a patient who cannot write because one of their intact skills was visual recognition and some simple reading. I wanted to springboard off those strengths to build on verbal expression (main goal of therapy). Plus, my hope is that by enhancing their semantic system, I’m increasing their speech motor programming (per Beeson et al 2002 Cognitive Model of Language Processing).

comparison for using act the Intended Way vs. a Modified way

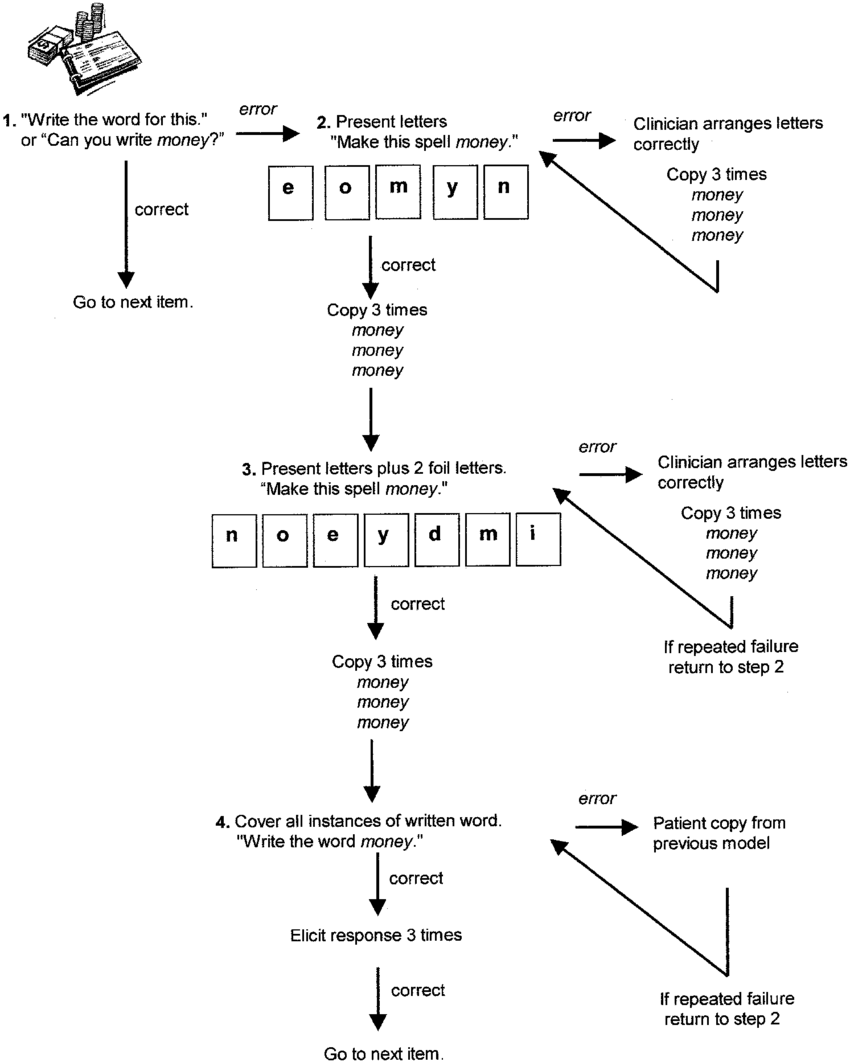

The actual ACT protocol:

Schematic representation of Anagram and Copy Treatment (ACT). From Beeson et al. 2002

Here’s one of the ways I modified ACT for a patient with global aphasia, verbal apraxia, and monoplegia of the right arm:

I show a picture of the target word and under that is the first letter and then blank spaces for the remaining letters. So if the picture was of a cat, then it would show C __ __ at the bottom.

I present the 3 letters (continuing the example of ‘cat’) and ask my patient to spell the target word. I point to my mouth so the patient can see my production (principle of apraxia treatment - I use it here, even when I’m not asking the patient to repeat it right now).

When the patient appears to finish arranging the letters, I notice that they sit back in their chair. They look at their work again and sometimes notice errors. Then they re-arrange the letter tiles. Sometimes, they’re successful. Sometimes, they need assistance. I prefer to give my patients the time and space to be problem solvers and if they appear to want help or become frustrated or impatient, then I assist. This places a bit more control in the hands of the patient as they are directing the amount of assistance they want.

Once we have the correct arrangement of the tiles, I place the word in a carrier phrase, and we work on verbal production.

When you compare ACT’s protocol with the version that I implemented - you can see it diverged on MANY aspects.

Here’s why:

I already established this patient cannot use their right hand. I did a few trials with their left and felt the goal wasn’t to get them to become proficient with writing with their non-dominant hand. This was confirmed by the patient and spouse. So the writing element was tossed. I am considering replacing the tile arranging with typing on a keyboard.

If the patient feels comfortable typing with one hand, then we might get a functional method for sending emails as a viable communication tool with family and friends. If typing simple messages becomes a viable option, I can circle back to AAC and trial some basic apps that focus on text to speech, rather than the current tool, which is a bit more involved and isn’t used.

This is just one example of how to modify EBP to fit your patient’s unique needs. I fully endorse and support hacking EBP when it’s for the cause of advancing patient-centered elements in therapy. Each of the changes I made were in response to (1) the patient’s residual fine motor skills (only focused on sliding tiles around with her left/non-dominant hand rather than implementing the writing component), (2) the patient’s strength of reviewing her work and recognizing errors (ability to self-monitor is a great boon for advancing therapy skills), and (3) the patient’s incredible perseverance and work ethic.

guides for implementing act (the intended way)

act research

Ball, A. L., de Riesthal, M., Breeding, V. E., & Mendoza, D. E. (2011). Modified ACT and CART in severe aphasia. Aphasiology, 25(6-7), 836-848.

Beeson, P. M. (1999). Treating acquired writing impairments: Strengthening graphemic representations. Aphasiology, 13, 767-785.

Beeson, P. M., Hirsch, F. M., & Rewega, M. A. (2002). Successful single-word writing treatment: Experimental analyses of four cases. Aphasiology, 14(4-6), 473-491.

Beeson, P. M., Rising, K., & Volk, J. (2003). Writing treatment for severe aphasia: Who benefits? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46, 1038-1060.

Raymer, A., Cudworth, C., & Haley, M. (2003). Spelling treatment for an individual with dysgraphia: Analysis of generlaisation to untrained words. Aphasiology, 17(6-7), 607-624.

CHECK OUT THE SPEECH UNCENSORED PODCAST

Covering all topics on the medical SLP scope of practice. Available for ASHA CEUs. Playing across all major podcast platforms (Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, etc.). New episodes weekly.