Hacking the ACT for High-Level Patients

The material on this page will only make sense if you have a pretty good understanding of where I stand on EBP, hacking EBP, and patient-centered care. If you’ve already read those posts, then keep right on going and scroll on down to the good stuff! If not, then I recommend reading these articles first by clicking the images.

comparison for using act the Intended Way vs. a Modified way

This is a case study of how I modified EBP to fit my patient’s unique needs. I fully endorse and support hacking EBP when it’s for the cause of advancing patient-centered elements in therapy.

Each of the changes I made were in response to (1) the patient’s main concern (reading, spelling, and writing), (2) the patient’s personal interests (I used a bank of words generated with the patient based on their family members’ names, work terminology, and hobbies), and (3) the patient’s capacity for challenge (when the patient became impatient or frustrated, I adapted the parameters).

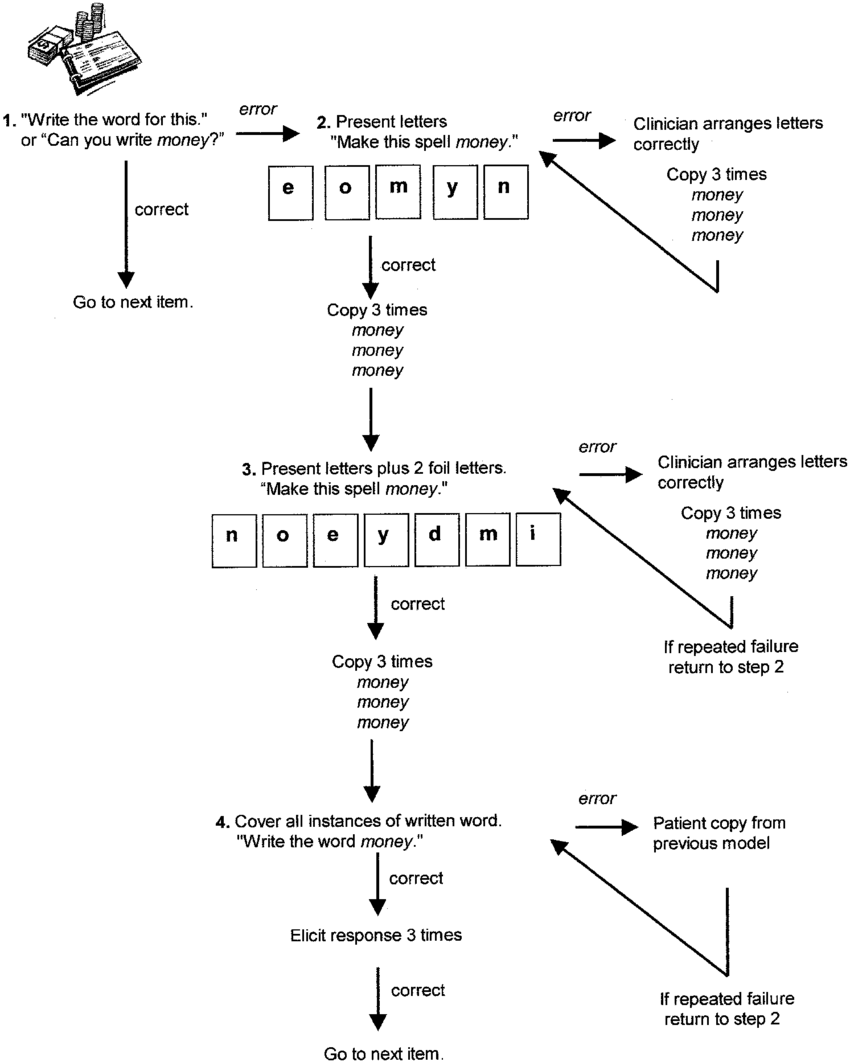

The actual ACT protocol:

Schematic representation of Anagram and Copy Treatment (ACT). From Beeson et al. 2002

Here’s a case study on how I’ve modified ACT for a high performer:

Generate a list of words and phrases based on the patient’s interests, hobbies, family, and work.

Lay out all the letter tiles on the table. Like, ALL of them. Every letter in the Scrabble/Bananagrams bag you have.

Ask patient to spell one of the words from the personalized word/phrase list.

If the patient struggles with scanning to find the tile, I assist as the main goal of the task isn’t scanning (but helpful for the patient to work on in this particular case).

If the tiles are arranged accurately, provide the next stimulus word.

If the patient makes an error, determine if pt was able to fix on their own or needs assistance to repair.

Once the word is spelled correctly with the tiles, ask the patient to write the word 3 times on a piece of paper (able to reference the tiles if needed)

My particular patient became increasingly frustrated with writing the word 3 times, so I started skipping this step.

Make a notation of words spelled incorrectly to use again next session.

When you compare ACT’s protocol with the version that I implemented - you can see it diverged on MANY aspects.

Write to dictation task at baseline and at post-treatment for the patient described in this post.

Here’s why:

This patient exhibited high personal expectations, impatience, and frustration.

I knew I couldn’t pre-select the tiles only to have the patient arrange them. They needed to have more control over the task. I only assisted providing the desired letter if the patient became impatient with scanning.

By having the patient search for the letters, I increased the complexity of the task. This allowed the patient to demonstrate the ability to identify and select the specific letters needed to spell the target word.

I decided to drop the “copy three times” portion because the patient became easily frustrated with any mistakes made during that part. Additionally, I was using a modified version of CART that addressed writing. So I knew the patient wasn’t missing out on orthographic opportunities.

By reading and responding to my patient’s emotional reaction to the tasks, and then making modifications, I hoped to maintain “buy-in” with therapy and build a strong therapeutic alliance.

Guides for implementing ACT (the intended way)

act research

Ball, A. L., de Riesthal, M., Breeding, V. E., & Mendoza, D. E. (2011). Modified ACT and CART in severe aphasia. Aphasiology, 25(6-7), 836-848.

Beeson, P. M. (1999). Treating acquired writing impairments: Strengthening graphemic representations. Aphasiology, 13, 767-785.

Beeson, P. M., Hirsch, F. M., & Rewega, M. A. (2002). Successful single-word writing treatment: Experimental analyses of four cases. Aphasiology, 14(4-6), 473-491.

Beeson, P. M., Rising, K., & Volk, J. (2003). Writing treatment for severe aphasia: Who benefits? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46, 1038-1060.

Raymer, A., Cudworth, C., & Haley, M. (2003). Spelling treatment for an individual with dysgraphia: Analysis of generlaisation to untrained words. Aphasiology, 17(6-7), 607-624.

CHECK OUT THE SPEECH UNCENSORED PODCAST

Covering all topics on the medical SLP scope of practice. Available for ASHA CEUs. Playing across all major podcast platforms (Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, etc.). New episodes weekly.